Bridging the Digital Access Gap: Fresh Perspectives on Challenges in Digital Inclusion

Think about your every day life and how many times you reach for technology to carry out day to day tasks. Simple things like check the weather, book a GP appointment, plan a trip to the theatre or just to keep in touch with friends and loved ones. Digital access and the ability to use technology are increasingly vital for navigating everyday life. But what about those who still struggle to keep up in our ever-digitizing world? A recent study by Wilson-Menzfeld et al. (2024) sheds light on digital exclusion in North East England, exploring who is most affected and why. This comprehensive research, blending survey data with focus group discussions, uncovers the realities of digital inequality and suggests ways forward for building more inclusive digital policies.

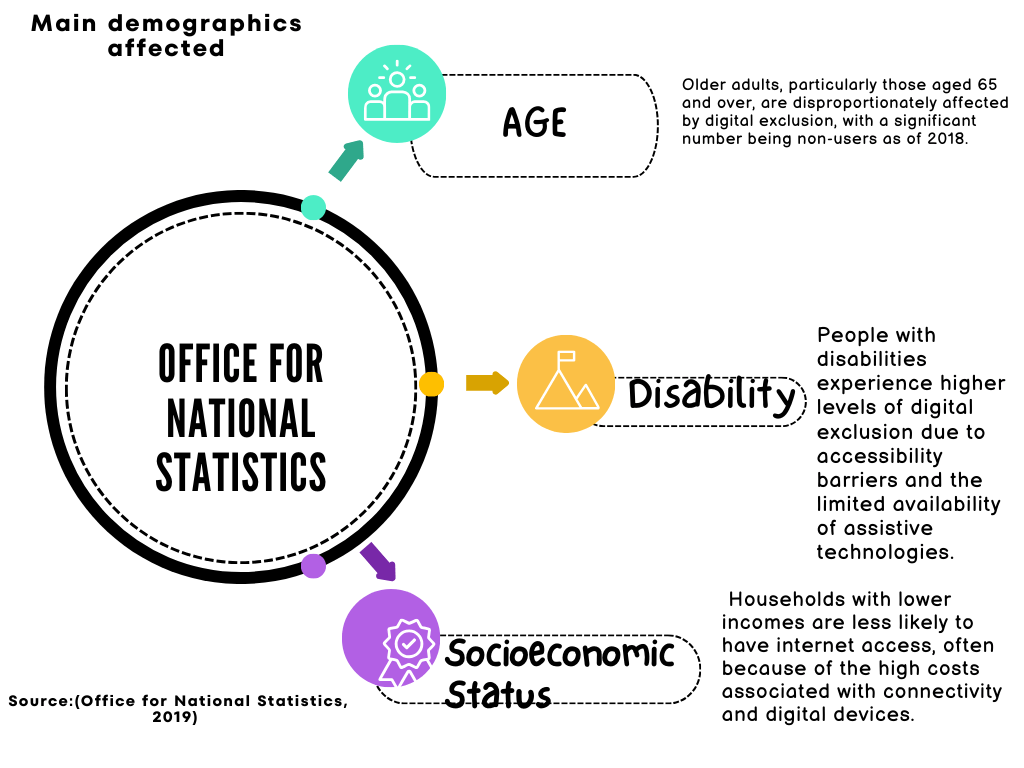

Driven by government initiatives promoting a “digital future,” digital accessibility is increasingly critical for engaging with essential services such as government programs, healthcare, education, and financial systems (Central Digital & Data Office, 2024). This trend raises significant concerns, as age and disability—key factors in digital exclusion—disproportionately affect the very social groups that depend most heavily on these services (House of Lords, 2023).

Who’s Missing Out on Digital Access?

Image created by author

The term “digital exclusion” goes beyond simple lack of internet access. It includes limited digital skills, confidence gaps, and barriers to everyday usage of technology. Wilson-Menzfeld’s study identified a surprising 12% of survey respondents as “digitally excluded.” Older adults, those on limited incomes, and people with less formal education were particularly affected. This issue often overlaps with other socio-economic factors, especially in areas where people already face financial struggles.

Interestingly, digital exclusion isn’t always linked to economic status alone. The study found that even in relatively high-income areas, some residents lack digital access or skills, suggesting that policies can’t just focus on general economic support but must address varied, community-specific needs.

Beyond Demographics: How Attitudes Shape Digital Inclusion

Image generated by WordPress AI

One fascinating finding of the study is that personal attitudes towards technology—how confident or willing someone is to use it—play a big role in whether they face digital exclusion. People who felt pushed to learn digital skills due to the pandemic, for example, were less likely to be excluded. Yet others, worried about privacy or uncomfortable with technology, were more reluctant to engage. This suggests that building digital confidence, perhaps through supportive educational programs, can be as important as providing access to devices and internet.

This supports the systematic review of the digital divide undertaken by Lythreatis et al.,( 2022) The research showed that when people expect good results from using the internet, they feel more confident in their ability to use it effectively.

Personal Stories Behind Digital Barriers

Image generated by Bing AI

Through focus groups, the study also explored the experiences of the people most affected by digital exclusion. Participants shared a variety of challenges that can limit technology adoption. Deaf individuals described the limited functionality of certain apps, especially transcription tools, and the high cost of mobile data.

If I go out, like, myself – I need to communicate with hearing people. I can sign, I can text … Text that down. And then they’ve got, like, speech to text on the phone. So, it’s like … Yeah, I never really knew about that until last year (P002, deaf community)

Most of the time it’s good, you know, if I’m talking about live, live transcript, yeah. Live transcript. It’s good, but it’s not perfect. Speech will come up on the screen, sometimes you get different words. Something you haven’t said […] There’s another problem that I have with that, I need to connect to Wi-Fi. Like, instead of data. Or Wi-Fi or data. So, there’s a limit on data. So, you can’t use it every time (P002, deaf community)

Women with histories of domestic violence shared how technology had empowered them but also made them feel vulnerable. Mobile banking, for instance, provided essential financial control, yet these tools could also pose risks if exploited by abusers.

I think it was having access to digital technology that actually managed to get me out of the relationship. Because I went onto Mumsnet. Which is … It’s anonymous. […] I didn’t even realise I was in an abusive relationship […] And I kind of got support from people. And they put me in touch with other organisations(Poo6 women’s Group

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0144929X.2024.2368087#d1e2127

Younger participants, who grew up with digital tools, showed high confidence levels in using them. But for some limited finances created barriers, such as when they could not afford to replace a broken device. These personal stories reveal the broad range of factors shaping digital use and remind us that inclusivity in technology is about more than just having the right tools.

Rethinking Digital Policies: A Call for Localized Solutions

The authors suggest that solutions to digital exclusion should go beyond broad, national policies. They argue that local, region-specific strategies are essential for meeting the varied needs of different communities. Older adults, for instance, might benefit from digital skills workshops, while younger, low-income residents may need affordable devices or internet access.

Furthermore, the study emphasizes that digital inclusivity is as much about social and cultural factors as it is about access. People who fear data privacy issues or mistrust digital platforms, for example, may need more guidance and transparency around online security to feel comfortable participating fully in digital life.

Moving Toward a Fairer Digital World

Image generated by Bing AI

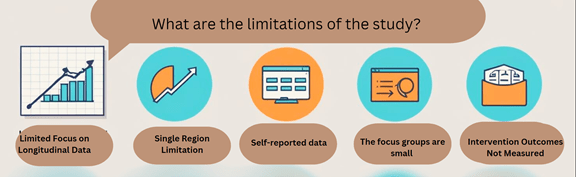

This study underscores a central point: digital exclusion isn’t a single-issue problem. It reflects and reinforces existing social inequalities. To build a fairer, more digitally inclusive society, we need to recognize the unique challenges and needs faced by various groups.

The study, while comprehensive, has several limitations. It lacks a longitudinal perspective, missing insights into changes in digital exclusion over time, and its findings are geographically specific, limiting generalizability to other regions or socio-economic contexts. The reliance on self-reported survey data introduces potential bias, and digitally excluded individuals may have been underrepresented due to the use of paper and online surveys. A broad definition of digital exclusion risks diluting specific insights into dimensions like access and skills. Furthermore, the small focus groups limit qualitative depth, and while the study identifies solutions, it does not evaluate their effectiveness. Future research should look to address these issues.

Image generated by WordPress AI

For academics, policymakers, and those in public services, this study’s findings serve as a reminder that we cannot adopt a one-size-fits-all approach to digital inclusion. Region-specific actions, more accessible technology, and tailored educational initiatives will help close the digital divide. As technology continues to shape how we live, inclusivity should be at the core of any digital transformation, ensuring that digital participation is a right, not a privilege.

To read the full study https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2024.2368087

References

Central Digital & Data Office. (2024). Transforming for a digital future: Government’s 2022 to 25 roadmap for digital and data. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/transforming-for-a-digital-future-governments-2022-to-25-roadmap-for-digital-and-data/transforming-for-a-digital-future-governments-2022-to-25-roadmap-for-digital-and-data

House of Lords. (2023). Digital exclusion. Communications and Digital Committee. London: Authority of the House of Lords. Retrieved from https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld5803/ldselect/ldcomm/219/219.pdf

Lythreatis, S., Singh, S. K., & El-Kassar, A.-N. (2022). The digital divide: A review and future research agenda. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 175, 121359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121359

Office for National Statistics. (2019, March 4). Exploring the UK’s digital divide. Retrieved from https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/householdcharacteristics/homeinternetandsocialmediausage/articles/exploringtheuksdigitaldivide/2019-03-04

Ofcom. (2022). Digital exclusion: A review of Ofcom’s research on digital exclusion among adults in the UK. Retrieved from https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0022/234364/digital-exclusion-review-2022.pdf

Van Deursen, A. J. A. M., & Van Dijk, J. A. G. M. (2019). The first-level digital divide shifts from inequalities in physical access to inequalities in material access. New Media & Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818797082

Wilson-Menzfeld, G., Erfani, G., Young-Murphy, L., Charlton, W., De Luca, H., Brittain, K., & Steven, A. (2024). Identifying and understanding digital exclusion: A mixed-methods study. Behaviour & Information Technology, 1(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2024.2368087

Leave a comment